25 Years of Linux

This year marks a major milestone for the internet, as well as for mobile and embedded computing. The Linux kernel, the software that drives large servers and small phones alike, is a quarter century old. Perhaps you’ve never heard of Linux, or are unaware of just how significantly it has transformed many areas of computing. Read on to learn how one person’s hobby project changed the world, redefining computing for an entire generation.

Humble Origins

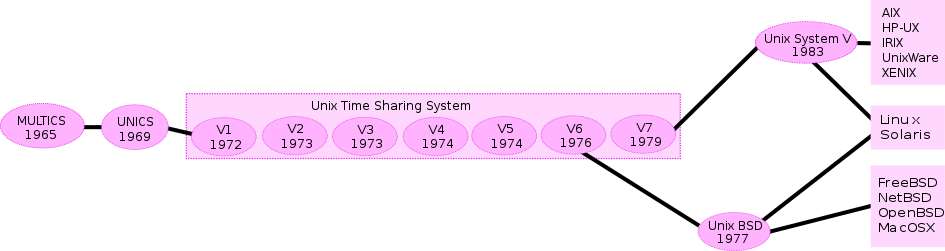

The world of computers was significantly different when Linux came into being. Personal computing was relatively new, gradually unseating the status quo of giant mainframes and dumb terminals. Mainframes and servers ran some variety of Unix, a powerful yet sophisticated operating system.

Unix had a complicated pedigree. Its ubiquity and familiarity led to many copies. One of which, BSD, was created in 1977 and released for free. Unfortunately, while BSD expanded Unix’s reach and penetration, it contained commercial code from AT&T’s proprietary Unix version, leading to a lawsuit that severely limited its use and development.

This uncertainty around BSD’s legality left an open void. Technicians wanted a freely available, familiar operating system that they could use in their labs and facilities. Two factors would combine to meet this need. In 1983, Richard Stallman birthed the Free Software movement, a savvy combination of politics and engineering to challenge the proprietary nature of developing and distributing software. The GNU project, one aspect of the Free Software movement, created freely available and distributable versions of the libraries and commands familiar to Unix users and developers. With the commands in place, all that was needed was a kernel to provide an open interface to the computer’s underlying hardware.

From USer:Bilou — Own Work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

In 1991, a young Finnish developer named Linus Torvalds created such a kernel. Naming it Linux, he’d hoped to use his current hardware with the then new 80386 processor. On August 25, 1991, the first version of Linux was announced publicly. An operating system is more than just a kernel. It also requires a set of userspace tools, commands for using the system along with tools for developing new capabilities. Linus leveraged GNU’s userspace, instantly empowering his hobby project with a familiar environment in which any modern Unix user was competent.

Instantly, the world’s many Unix users had a clear rallying point. Because the kernel was written entirely from scratch, it bypassed the legal entanglements that snagged BSD and rendered its future uncertain. Use of the GNU userspace offered a complete environment that would have been impossible for one person to write alone. In the intervening years, the Linux kernel would acquire a vast community of thousands of developers. It would grow so large that it changed how vast distributed teams build software, spawning the Git revision control system in an attempt to manage large-scale collaboration. Ultimately, the Linux kernel and userspace would scale both up and down, driving both the largest data centers and the smallest embedded devices with equal ease and sophistication.

Running Linux

Linux’s greatest strength and weakness is that it is simultaneously one thing and many, simultaneously everything and only a small part of the whole. Try to download Linux and you won’t find it easily, yet you probably interact with it thousands of times daily without even knowing it. You may even have Linux on the phone in your pocket, running in your television, or controlling your home router.

Unlike other operating systems, the fact that Linux is just a kernel makes it difficult to use on its own. You download Linux by obtaining a distribution, a version of the kernel and userspace plus additional tools that are neatly packaged for installation on a device. To complicate matters further, some distributions repackage the work of other distributions, further refining their functionality and interface to meet specific needs. For instance, one Linux distributor may package a mainstream distribution specifically for educators, introducing applications and features that make Linux more appropriate for the classroom.

A full discussion of Linux distributions would be exhaustive. However, here are some of the most common flavors from which others descend, along with some outliers that defy easy categorization.

Debian

One of the earliest Linux distributions, Debian derives its name from its founder Ian Murdock and his wife, Debora. One of Debian’s strong tenets is its preference for Free Software, and it strives to remain faithful to its GNU origins. Debian was one of the first Linux distributions to use a packaging system, shipping pre-compiled software that did not need to be built from source whenever it was used.

Debian spawned many distributions. Perhaps the most well-known of these, Ubuntu, was created by a commercial company in 2004. Ubuntu broke somewhat from Debian’s Free Software origins, commercializing Linux and introducing official paid support channels. Ubuntu is also available on phones, tablets, and other form factors where Debian has yet to go.

Red Hat

Another early Linux distribution, Red Hat, was of a decidedly more commercial leaning than Debian. Red Hat pioneered commercial sales of Linux itself, and the aspiring home user could purchase an official CD and professionally printed user manual on computer store shelves in the mid to late 90s. This made Linux like other operating systems that were available for purchase.

Like Debian, Red Hat originated many distributions. Perhaps the most well-known of these are Fedora and CentOS. Like Debian, Fedora emphasizes open source software and community use. CentOS trends more toward enterprise use, with longer support cycles and commercial customers in mind.

Slackware

No discussion of Linux distributions would be complete without Slackware. Perhaps the first ever Linux distribution, Slackware was how the earliest users booted the combined kernel and userspace on their computers.

While other distributions have gained more polish over the years, Slackware remains close to its roots. Slackware is the classic car of Linux distributions. No one runs it just to get work done, and those who do are prepared to tinker and tweak until their systems run smoothly.

Android

Android needs no introduction, but many of its users may not realize that it is powered by the Linux kernel. Access your Android phone as an app developer would, and you’ll find a minimal userspace underneath all the apps and polish.

Android is not the only mobile platform based on Linux. Tizen, a less popular mobile operating system, is also based on Linux. Linux also runs in many embedded devices such as stereos and televisions, with a thin custom user interface hiding its complexity. Because of its permissive license and developer friendly interface, Linux is a great candidate for the basis of any embedded computing environment or mobile device.

Conclusion

“I’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones.” So read Linus’ original announcement 25 years ago. Today Linux is quite large, extremely professional, and drives much of the

Call us at 1-888-GTCOMM1

Call us at 1-888-GTCOMM1